Emily Brontë: The Enigmatic Genius Behind Wuthering Heights

Emily Jane Brontë, born on 30th July 1818, at 72-74 Market Street in Thornton, West Yorkshire, is one of the most celebrated and enigmatic figures in English literature. Best known for her singular gothic novel, Wuthering Heights, first published in December 1847, Emily’s life was marked by solitude, creativity, and an intense connection to the natural world around her. While she left behind only one novel and a small body of poetry following her death, her literary legacy is profound, influencing generations of writers and readers alike to this day. Her life, though brief, was one of immense intellectual and imaginative power, and her work continues to captivate modern readers with its emotional depth, psychological complexity, and the raw portrayal of human passion.

Early Life and Family

Emily was the fifth of six children born to the Reverend Patrick Brontë and Maria Branwell. Patrick, originally a native of Imdel, County Down, Ireland, was an Anglican clergyman who has risen from very humble beginnings to study theology at St John’s College, Cambridge via a scholarship. Maria came from a respectable Cornish merchant family in Penzance. The Brontës lived modestly, and their early years were marked by both creativity and tragedy. In January 1820 Patrick was appointed the perpetual curate of St Michael and All Angels’ Church in the small village of Haworth. So when Emily was just two years old, the family, along with their two young servant sisters, Nancy and Sarah Garrs, travelled six miles across the rugged moors from Thornton to their new home. The isolated parsonage, surrounded by the bleak yet beautiful Yorkshire countryside, would become Emily’s lifelong home and sanctuary, its setting shaping much of her imagination.

In September 1821, when Emily was only three, her mother died of suspected uterine cancer following a long illness, leaving the Brontë children—Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, and Anne—in the sole care of their devastated father. Soon after Maria’s sister, Elizabeth Branwell, who had nursed Maria through the later stages of her illness made the permanent 400 mile trip from her home in Penzance to Haworth in order to help Patrick run the house and look after his children, she would remain there for the rest of her life. This tragic loss had a profound effect on the family, and grief became a constant companion for the Brontë children. Despite this shadow, their home was a vibrant place of intellectual and creative activity. Patrick encouraged his children’s education and allowed them the freedom to explore literature, politics, and philosophy.

The Brontë Children’s Imaginary Worlds

Emily, along with her siblings, exhibited a remarkable imagination from a young age. The children created elaborate fictional worlds, which they called “Angria” and “Gondal,” where they invented characters, wrote stories, and developed intricate political and romantic sagas. Charlotte and Branwell were primarily responsible for Angria, while Emily and Anne later broke away and created the world of Gondal. This world-building was not merely childhood play; it was a serious and immersive creative process that allowed the Brontë children to express their emotions, intellects, and imaginative powers in ways they could not in the isolation of the real world.

The Gondal sagas, in particular, offered Emily an early outlet for the themes that would later dominate her writing. These stories of wild, passionate characters living in remote and untamed landscapes, fuelled by stories of Byronic heroes, reflected Emily’s inner world. Gondal was a lifelong obsession and a place where Emily could explore the concepts of love, power, revenge, and the sublime connection between humanity and nature—ideas that would later be central to her novel Wuthering Heights.

Education and Attempts at Employment

Emily’s formal education was sporadic and marked by difficulty. In November 1824, when she was six, Emily was sent to the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge in Lancashire, a harsh institution with poor sanitary conditions. Her older sisters, Maria, Elizabeth and Charlotte were already pupils here. The school was a deeply unpleasant experience for all the Brontë girls. In mid February 1825 Maria was diagnosed with tuberculosis following a severe typhoid outbreak at the school and was returned to Haworth. Her condition deteriorated and she died on the 6th May aged eleven. Later that month Elizabeth began to show the same symptoms as her older sister and was rushed home, only to also die from tuberculosis on the 15th June. Greatly fearing for Charlotte and Emily, Patrick rushed to remove them home as well and they were never to return to Cowan Bridge. Charlotte later used this experience as the basis for Lowood School in Jane Eyre. In particular the loss of Maria was devastating for the family still reeling from the loss of their beloved mother only a few years earlier. Sweet and intelligent Maria had become the mother figure her younger siblings craved and was the apple of her father’s eye.

For Emily, the traditional routes available to women of her social standing—teaching or becoming a governess—were unappealing. However, financial necessity required her to try. In 1835, Emily briefly attended Roe Head School in Mirfield run by Margaret Wooler, where Charlotte was a teacher. But Emily’s intense homesickness and aversion to the restrictive school environment made her stay unbearable, and she returned to Haworth after just a few months. Her return to the familiar sanctity of the parsonage and the freedom of the moors seemed essential to her well-being.

In September 1838, Emily briefly took up a position as a teacher at Miss Patchett’s Law Hill School in Halifax. Once again, her solitary nature and longing for home made the experience intolerable, and she left after seven months. Emily’s health and temperament were ill-suited to the roles of governess or teacher, both of which demanded constant social interaction and subjugation of her own creative impulses. Her brief attempts at employment only served to reinforce her need for solitude and her strong connection to her home and the moors.

The thought of Charlotte, Emily and Anne opening a small school themselves in Haworth had been an idea for some time and so in February 1842, Emily and Charlotte travelled to Brussels to attend the Pensionnat Heger, a boarding school where they could study French, German, and literature. While Charlotte found intellectual stimulation in their new enviroment, Emily soon longed for home and was largely indifferent to the cultural life of the city. She saw little value in conforming to societal expectations or foreign ideals of education, though she still managed to impress Constantin Heger with her analytical mind. However in late October of that year their aunt Branwell died due to complications related to a bowel obstruction, the news only reaching the sisters after her burial and they immediately returned home.

Emily’s Poetry and the Discovery of Her Talent

Despite her reclusive nature, Emily was a prodigious poet. From a young age, she filled notebooks with poems that expressed her deep connection to nature, her profound sense of solitude, and her introspective reflections on life and death. Her poetry is often marked by its intense emotionality, its preoccupation with the spiritual and the sublime, and its exploration of human suffering and transcendence.

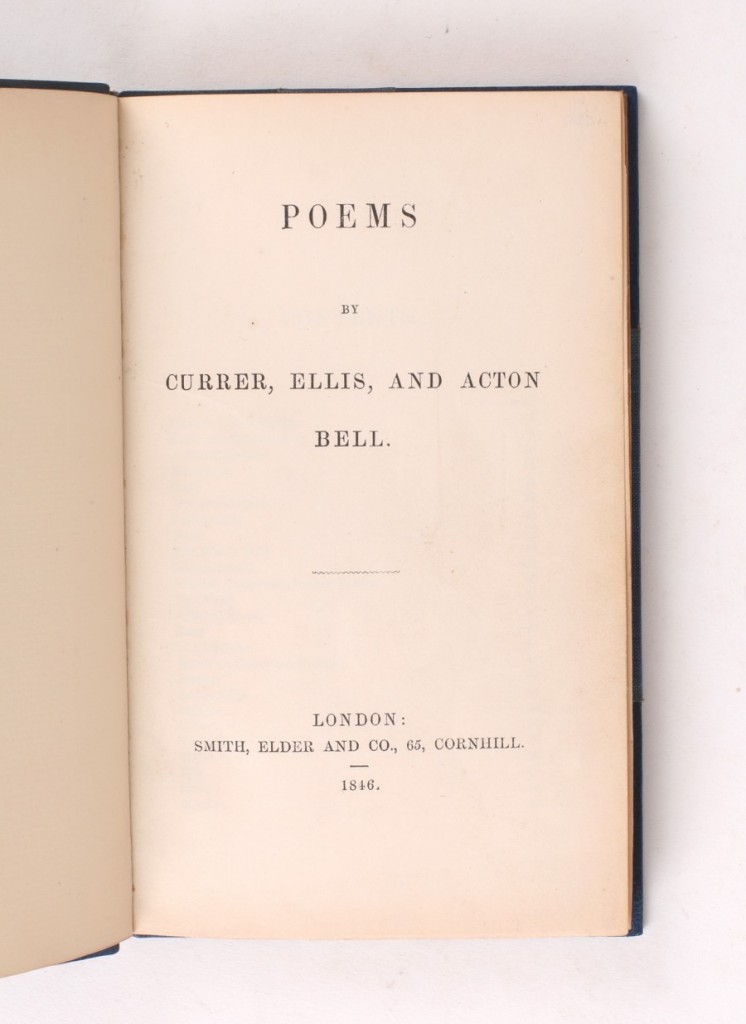

In the autumn of 1845, Charlotte discovered a notebook of Emily’s poems and was utterly struck by their originality and power. A furious Emily was enraged by this intrusion into her private world, but eventually Charlotte persuaded her and Anne to join her in trying to publish a combined collection of their work. Aunt Branwell had left most of her money in her Will to the sisters, so in May 1846, Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell was published by Aylott & Jones of Paternoster Row, London. They used male pseudonyms to avoid the prejudice against women writers at the time. Although the collection sold only two copies in its first year and was therefore a commerical failure, it marked the beginning of Emily’s public literary career.

Emily’s poetry is now recognized as some of the most original and moving of the 19th century. Her verse is characterized by a strong connection to the natural world and an almost mystical sense of the individual’s place within it. Poems such as “No Coward Soul Is Mine” and “The Night-Wind” reveal her deep spiritual convictions, her belief in the power of the imagination, and her refusal to submit to conventional religious or social doctrines. Emily’s poetry, much like her novel, is suffused with an intense emotional energy and a profound sense of the individual’s struggle against societal and natural forces.

Wuthering Heights: A Masterpiece of Passion and Isolation

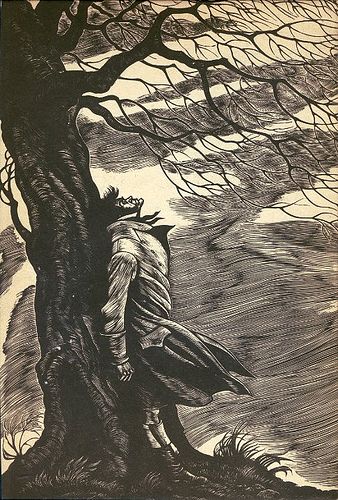

In December 1847, Emily published her only novel, Wuthering Heights. Initially met with confusion and even shock by critics and readers, Wuthering Heights has since become one of the most celebrated works in English literature. The novel, set against the wild and desolate Yorkshire moors, tells the story of Heathcliff, a dark and vengeful orphan, and his passionate, destructive love for Catherine Earnshaw.

Wuthering Heights is far from a conventional Victorian novel. Its narrative structure is complex, with multiple narrators recounting the story through layers of flashbacks and unreliable perspectives. The novel’s themes of love, revenge, social class, and the supernatural set it apart from other works of its time. Its portrayal of raw, violent emotions and morally ambiguous characters challenged the moral and social norms of Victorian society.

At its core, Wuthering Heights is a novel about the elemental forces of love and hate. Heathcliff and Catherine’s relationship is one of profound intensity and ambivalence. Their love defies conventional morality and transcends even death, but it is also a source of pain, destruction, and cruelty. The novel’s portrayal of their relationship has fascinated and perplexed readers for generations. Is Heathcliff a tragic hero, driven by his love for Catherine, or is he a monster, consumed by vengeance and hatred? Is Catherine a victim of her own passions, or is she complicit in the novel’s cycle of violence and suffering?

The setting of the novel—the wild, untamed moors—mirrors the emotional landscape of the characters. The moors, with their stark beauty and unpredictable weather, are both a refuge and a prison for the inhabitants of Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange. The isolation of the setting reflects the isolation of the characters, who are cut off from conventional society and governed by their own internal forces.

The novel’s reception was mixed when it was first published. Some critics were disturbed by its brutality and lack of moral resolution, while others admired its originality and emotional intensity. Over time, however, Wuthering Heights gained recognition as a masterpiece of English literature, praised for its innovative narrative structure, its exploration of the darker aspects of human nature, and its portrayal of the sublime in both nature and human emotion. Sadly Emily would not live to see its success.

Emily Brontë’s Personality and Private Life

Emily remains one of the most elusive figures in literary history. Unlike Charlotte, who had a more public literary career following Jane Eyre and her later novels, Emily shunned attention and preferred the quiet solitude of home. Descriptions of Emily from those who knew her paint a picture of a deeply private, strong-willed, and intensely intelligent woman. She was known for her physical strength and her love of nature, often taking long walks across the moors with her beloved bull mastiff cross-breed, called Keeper.

Emily’s reclusiveness was not merely a preference but a necessity for her creative process. The isolation of Haworth and the freedom of the surrounding moors were essential to her imaginative life. While Charlotte in particular sought fulfilment through her public literary career, Emily remained content in her solitary existence, devoted to her family, her home, and her writing.

Illness and Death

In September 1848, Emily’s beloved brother, Branwell, died after a long struggle with alcoholism and opium addiction. Emily, who had always been especially close to Branwell, was devastated by his death. Shortly afterward, Emily herself fell ill, likely with tuberculosis, a disease that had claimed the lives of her sisters Maria and Elizabeth years earlier. True to her nature, Emily refused medical intervention and resisted any suggestion that she was seriously ill. She continued to care for her father and maintain the household duties, even as her health deteriorated.

Emily Brontë died on the 19th December 1848, at the age of 30. Her death, like much of her life, was marked by her fierce independence and refusal to submit to conventional expectations. She was buried in the family vault at St. Michael and All Angels Church in Haworth, close to the home and the moors she had loved so deeply.

Legacy

Though she published only one novel, Emily Brontë’s legacy is immeasurable. Wuthering Heights is now regarded as one of the greatest novels in the English language, admired for its bold narrative structure, its exploration of the human psyche, and its passionate, unflinching portrayal of love and revenge. Emily’s poetry, too, is celebrated for its emotional depth, its spiritual intensity, and its connection to the natural world.

Emily Brontë remains a singular figure in the history of literature—an author whose work defied the conventions of her time and whose genius continues to resonate with readers and writers today. Her life, like her novel, was one of passion, solitude, and an unyielding commitment to her own vision. In Wuthering Heights, Emily captured the wild, untamable forces of nature and human emotion, leaving behind a work that transcends time and continues to inspire, challenge, and move those who encounter it.