In the annals of English literature, the Brontë family name glows with a peculiar intensity—three sisters who transformed their isolation and suffering into stories that echo through generations. But behind the brilliance of Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, lies a quieter, more tragic figure: Maria Brontë, the eldest daughter of Patrick and Maria Brontë. Though she died young, Maria’s brief life and premature death cast a long shadow over her siblings—and played a powerful, if indirect, role in shaping their emotional and creative worlds.

A Brief, Bright Life

Maria Brontë was born in early 1814, the first of six children to Reverend Patrick Brontë and his wife Maria Branwell Brontë. As the eldest child, Maria naturally assumed a maternal and intellectual role within the family. By all accounts, she was a thoughtful, sensitive, and deeply intelligent girl. Her younger siblings looked up to her, especially Charlotte, who later described Maria as possessing “extraordinary intelligence” and “singular sweetness of temper.”

After the death of their mother in September 1821, when Maria was only seven, the Brontë children were left in the care of their aunt, Elizabeth Branwell, following her moving from her native Penzance. However, it was Maria who stepped in to offer comfort and guidance to her siblings. Charlotte later recalled how Maria tried to soothe her grief by explaining their mother’s death in gentle terms: “She told me to pray and to trust in God.” Even as a child, Maria had a precocious moral and emotional awareness that helped bind the family in their early grief.

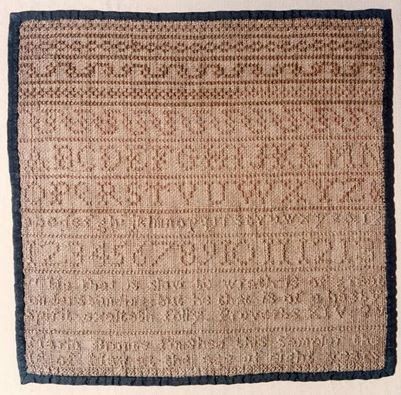

Image courtesy of the Bronte Society.

The Calamitous School Years

In 1824, Patrick Brontë sent his four eldest daughters—Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, and Emily—to the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge in Lancashire. The school, intended to provide an affordable education to the daughters of clergymen, turned out to be a place of suffering and neglect. It was underfunded, poorly heated, unsanitary, and rife with disease. The food was meager and spoiled, and the strict religious discipline bordered on cruelty.

Maria, already physically fragile, began to succumb to the harsh conditions. She developed tuberculosis—a disease that would later haunt the entire family. Patrick Brontë was finally called to the school when it became clear that Maria was dying. She was brought home to Haworth, where she died on 6th May, 1825, at the age of 11. Only weeks later, her sister Elizabeth would also die from the same illness, exacerbated by the school’s dire conditions.

The Emotional Earthquake

Maria’s death was more than a personal tragedy; it marked a turning point in the Brontë household. It shook the foundations of an already grief-stricken family. Patrick immediately withdrew Charlotte and Emily from the school. The surviving children were now educated at home in a cloistered and imaginative environment that would later serve as the crucible of their creative genius.

Charlotte, who was just nine when Maria died, never forgot the impact of losing her sister. In fact, scholars have long pointed to Maria as a model for the character of Helen Burns in Jane Eyre—the saintly, suffering schoolgirl who endures cruelty with Christian patience and ultimately dies of consumption. Helen’s spiritual serenity and moral conviction are widely seen as an idealized portrait of Maria.

Maria’s death naturally profoundly affected Patrick, who never fully recovered from the trauma of losing two daughters in such quick succession. His initial decision to send the girls to Cowan Bridge—a choice motivated by financial necessity and a desire to provide them with a respectable education—haunted him for the rest of his life. In later years, Patrick became increasingly protective of his remaining children, particularly his daughters, allowing them unprecedented freedom for young Victorian women to read widely, write freely, and develop their imaginations at home. This tragic event likely contributed to his liberal attitude toward his daughters’ literary pursuits, which was highly unusual for a man of his time and profession. In this way, Maria’s death not only changed the emotional dynamic of the family but also altered the practical course of the Brontës’ intellectual development, allowing their creative potential to flourish in a sheltered yet intellectually rich domestic world.

This emotional imprint—the grief, the injustice, the exposure to premature death—would seep into the works of all three sisters. Themes of mortality, illness, oppressive institutions, and the quiet strength of women in adversity became central to their fiction. It is no exaggeration to say that Maria’s death changed the trajectory of their inner lives and outward stories.

A Legacy Etched in Silence

What Maria might have become had she lived is a tantalising question. Given her precocious mind and gentle authority, she might have been the first Brontë to publish, or she may have become the glue that held the family together longer. But perhaps her greatest legacy was the emotional and intellectual spark she left behind.

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne grew up with an acute sense of life’s fragility—a quality that intensified their imaginations and sharpened their emotional sensitivity. They created entire worlds in the moors of Yorkshire, drawing from the deep wells of loss and longing left by Maria’s absence. The dreamscapes of Gondal and Angria, their childhood fantasy kingdoms, were as much escapism as they were homage to a lost sister.

Even in death, Maria shaped the Brontë narrative. She was the first to suffer for education, the first to fall to illness, and the first to leave a spiritual and moral legacy behind. Her life, though short, left an indelible mark on the emotional blueprint of some of the greatest novels in English literature.

Conclusion: The Sister Who Started It All

Maria Brontë never wrote a novel, never saw adulthood, and never experienced the fame her sisters would one day know. Yet her influence reverberates through every line of their work. She was the first to guide them, the first to suffer, and the first to show them the quiet power of endurance. In the silence of her absence, Maria helped give voice to some of the most haunting and enduring literature the world has ever known.

Her story is a poignant reminder that even the briefest lives can cast the longest shadows.